Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Development of Joint Action: Years 1-2

Development of Joint Action: Years 1-2

[email protected]

Inconsistent Triad #2

1. One- and two-year-olds are capable of performing joint actions.

2. All joint action involves shared intention.

3. A function of shared intention is to coordinate two or more agents’ plans (as Bratman’s account implies).

No planning ...

... So which joint actions can one- and two-year-olds perform?

‘By 12–18 months, infants are beginning to participate in a variety of joint actions which show many of the characteristics of adult joint action.’

Carpenter, 2009 p. 388

4-6 months

dyadic interactions

6-12 months

triadic interactions

~ 12-24 months

infants initiate and re-start joint actions

e.g. ‘peek-a-boo; tickle; rhythmic games; chase’

Brownell, 2011

drumming together

(from two years of age; Endedijk et al, 2015)

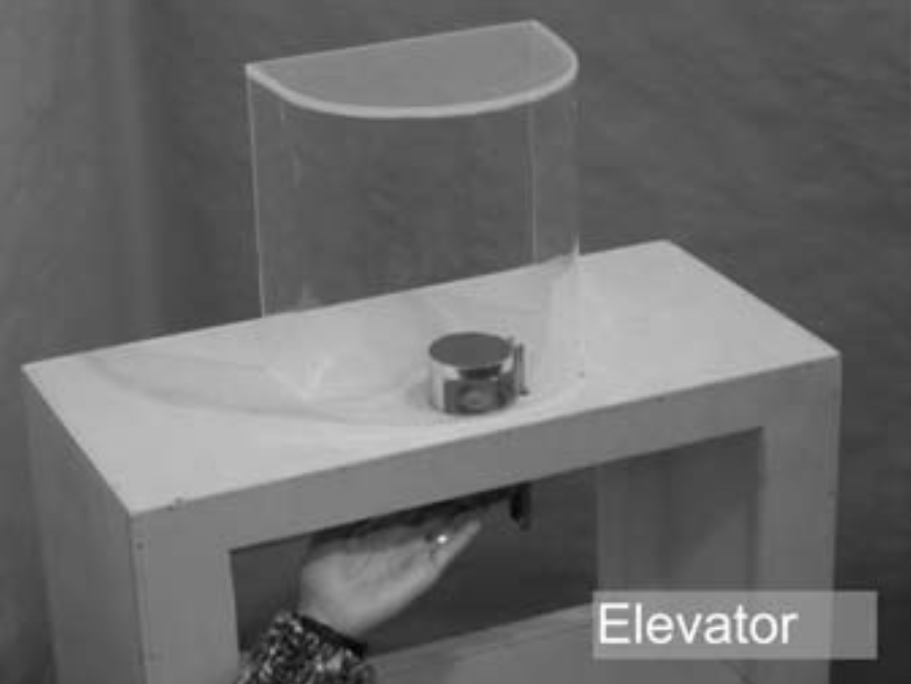

Warneken and Tomasello, 2006

Warneken and Tomasello, 2006

Warneken and Tomasello, 2006

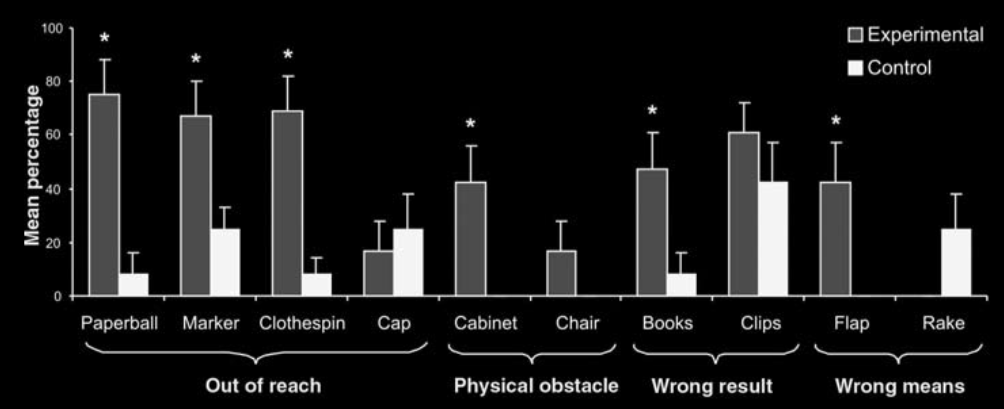

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 figure 2 (part)

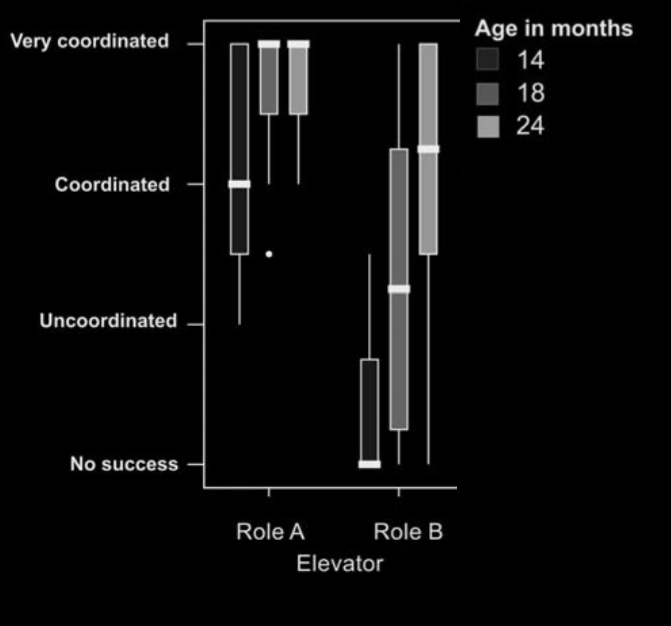

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 figure 3 (part)

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 figure 2 (part)

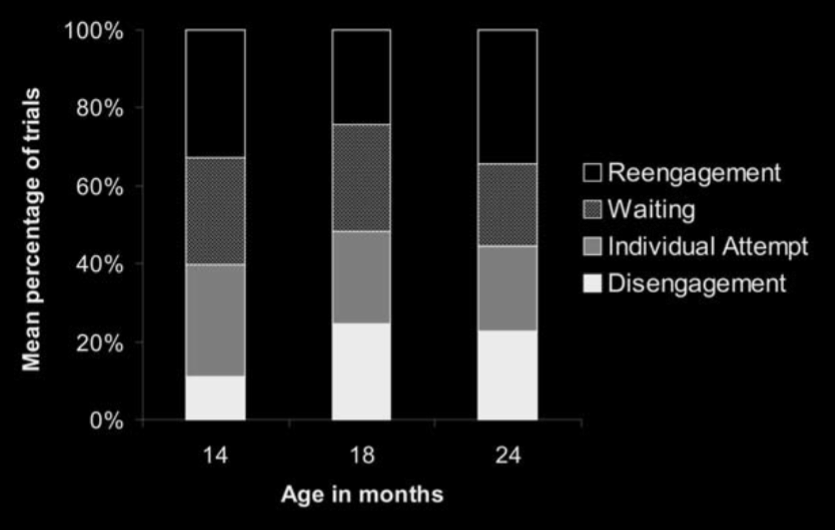

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 figure 4

Infants’ ‘attempts to reactivate the partner in interruption periods indicate that they were aware of the interdependency of actions—that the execution of their own actions was conditional on that of the partner’

‘these instances might also exemplify a basic understanding of shared intentionality’

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 pp. 290-1

Inconsistent Triad #2

1. One- and two-year-olds are capable of performing joint actions.

2. All joint action involves shared intention.

3. A function of shared intention is to coordinate two or more agents’ plans (as Bratman’s account implies).

Joint Action in Years 1-2

In the first and second years of life,

there is joint action

but it does not appear to involve planning agency

or shared intention.

Bratman’s account does not characterise

the sort of joint actions

infants perform in the first and second years of life.

How else might their joint actions be characterised?