Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

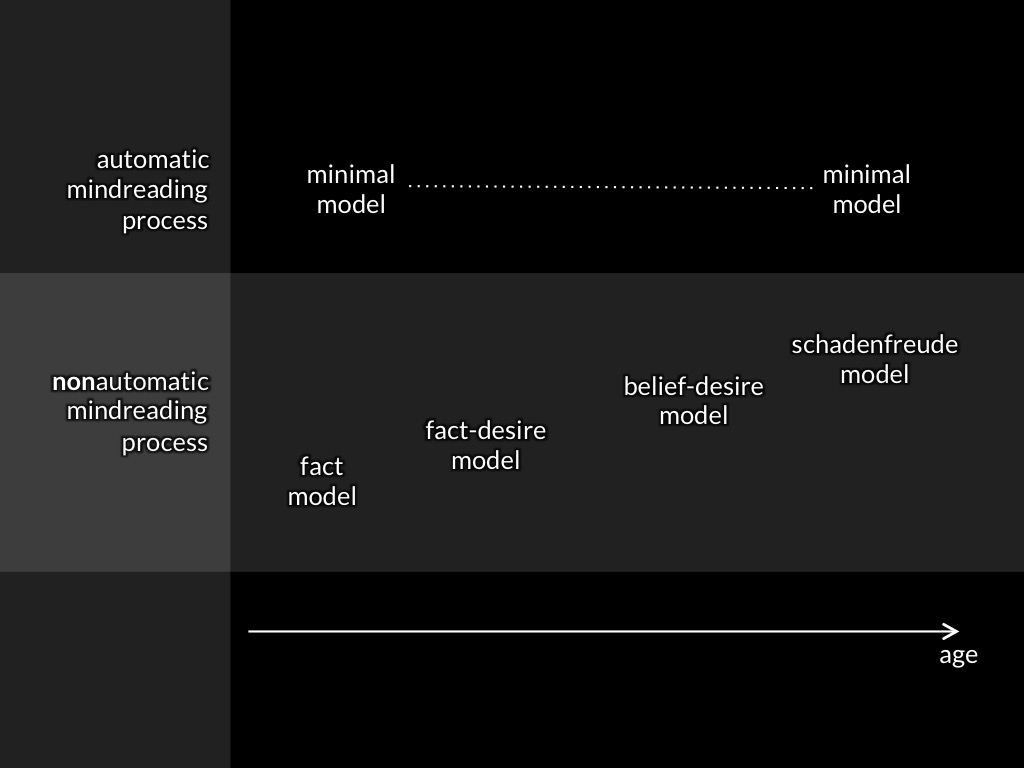

Conclusion: Models and Processes

conclusion

of mindreading.

Q1

How do observations about tracking support conclusions about representing models?

Q2

Why are there dissociations in nonhuman apes’, human infants’ and human adults’ performance on belief-tracking tasks?

A-tasks

Children fail

because they rely on a model of minds and actions that does not incorporate beliefs

non-A-tasks

Children pass

by relying on a model of minds and actions that does incorporate beliefs

dogma

the

of mindreading