Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

| lecture(s) | topic |

| 01 | Methodological Foundations and the Philosophy of Cognitive Development |

| 02 | Goal Tracking (& Mirror Neurons) |

| 03 & 04 | Knowledge of Mind |

| 05 | Physical Objects |

| 06 | Is There a Role for Metacognitive Feelings in Development? |

| 07 | Joint Action |

| 08 | Nonverbal Communication |

| 09 | Knowledge of Syntax (and Innateness) |

challenge

Explain the emergence in development

of mindreading.

The challenge is to explain the developmental emergence of mindreading.

Let me explain.

_Mindreading_ is

the process of

identifying mental states and purposive actions

as the mental states and purposive actions of a particular subject.

Researchers sometimes use the term ‘theory of mind’.

‘In saying that an individual has a theory of mind, we mean that the individual imputes mental states to himself and to others’

(Premack & Woodruff, 1978, p. \ 515)

(Premack & Woodruff 1978: 515)

So, to be clear about the terminology, to have a theory of mind is just to be able to

to mindread,

that is, to identify mental states and purposive actions

as the mental states and purposive actions of a particular subject.

So the challenge is to explain the emergence of mindreading.

You know (let's say) that Ayesha belives Beatrice is in the library.

Humans are not born knowing individuating facts about others' beliefs.

How do they come to be in a position to know such facts?

Meeting this challenge initially seems simple.

But, as you'll see, we quickly end up with a puzzle.

I think this puzzle requires us to rethink what is involved in having a conception of

the mental.

I shall focus on awareness of others' beliefs to the exclusion of other mental states.

There's no theoretical reason for this; it's just a practical thing.

And what we learn about belief will generalise to other mental states.

belief

How can we test whether someone is able to ascribe beliefs to others?

Here is one quite famous way to test this, perhaps some of you are even aware of it

already.

Let's suppose I am the experimenter and you are the subjects.

First I tell you a story ...

‘Maxi puts his chocolate in the BLUE box and leaves the room to play. While he is away (and cannot see), his mother moves the chocolate from the BLUE box to the GREEN box. Later Maxi returns. He wants his chocolate.’

In a standard \textit{false belief task}, `[t]he subject is aware that he/she and

another person [Maxi] witness a certain state of affairs x. Then, in the absence of

the other person the subject witnesses an unexpected change in the state of affairs

from x to y' \citep[p.\ 106]{Wimmer:1983dz}. The task is designed to measure the

subject's sensitivity to the probability that Maxi will falsely believe x to obtain.

I wonder where Maxi will look for his chocolate

‘Where will Maxi look for his chocolate?’

Wimmer & Perner 1983

Two models of minds and actions

Maxi wants his chocolate.

Maxi wants his chocolate.

Maxi believes his chocolate is in the blue box.

Maxi’s chocolate is in the green box.

Maxi will look in the blue box.

Maxi will look in the green box.

How can we test whether someone is able to ascribe beliefs to others?

Here is one quite famous way to test this, perhaps some of you are even aware of it

already.

Let's suppose I am the experimenter and you are the subjects.

First I tell you a story ...

‘Maxi puts his chocolate in the BLUE box and leaves the room to play. While he is away (and cannot see), his mother moves the chocolate from the BLUE box to the GREEN box. Later Maxi returns. He wants his chocolate.’

In a standard \textit{false belief task}, `[t]he subject is aware that he/she and

another person [Maxi] witness a certain state of affairs x. Then, in the absence of

the other person the subject witnesses an unexpected change in the state of affairs

from x to y' \citep[p.\ 106]{Wimmer:1983dz}. The task is designed to measure the

subject's sensitivity to the probability that Maxi will falsely believe x to obtain.

I wonder where Maxi will look for his chocolate

‘Where will Maxi look for his chocolate?’

Wimmer & Perner 1983

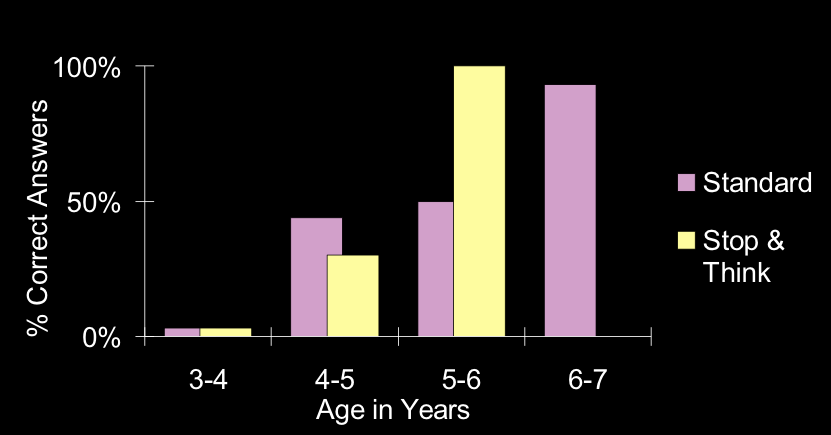

Here's the really surprising thing.

Children do really badly on this until they are around four years of age.

And they seem to develop the ability to pass this task only gradually, over months or years.

(There's something else that isn't surprising to most people but should be: adult humans not only nearly always provide the answer we're calling 'correct': they also believe that there is an obviously correct answer and that it would be a mistake to give any other answer. I'll return to this point later.)

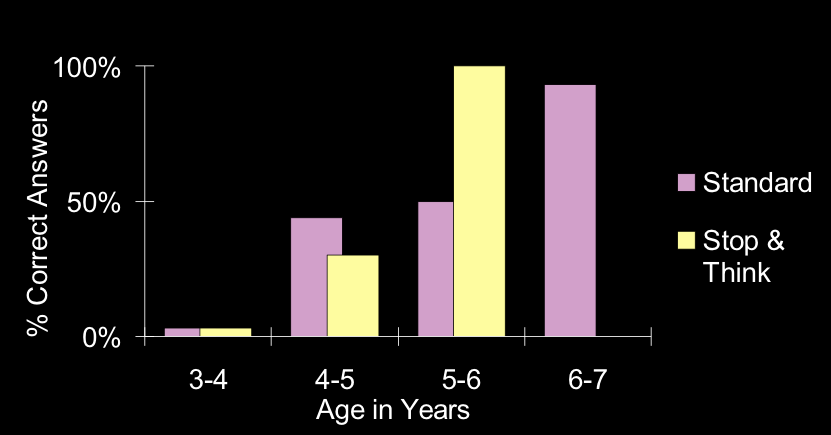

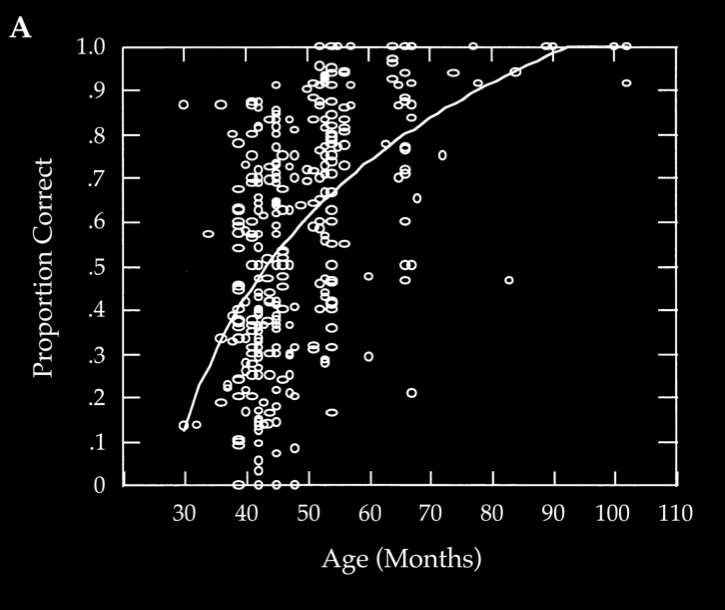

Wimmer & Perner, 1983

(NB: The figure is not Wimmer & Perner's but drawn from their data.)

So in terms of my two models,

it looks like 3 year olds are relying on a fact model

and only the older children are relying on a belief model.

Two models of minds and actions

Maxi wants his chocolate.

Maxi wants his chocolate.

Maxi believes his chocolate is in the blue box.

Maxi’s chocolate is in the green box.

Maxi will look in the blue box.

Maxi will look in the green box.

There's been some stuff in the press recently about bad science, mainly some dodgy methods and failures to replicate.

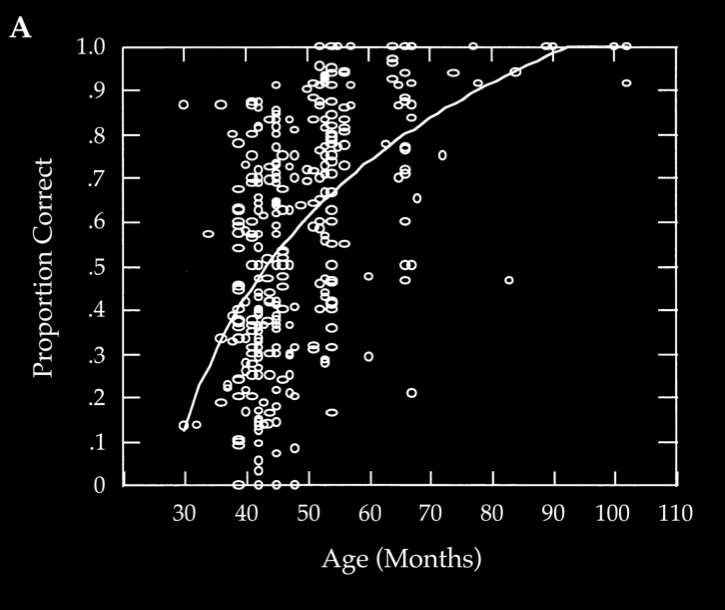

So you'll be pleased to know that a meta-study of 178 papers confirmed Wimmer & Perner's findings.

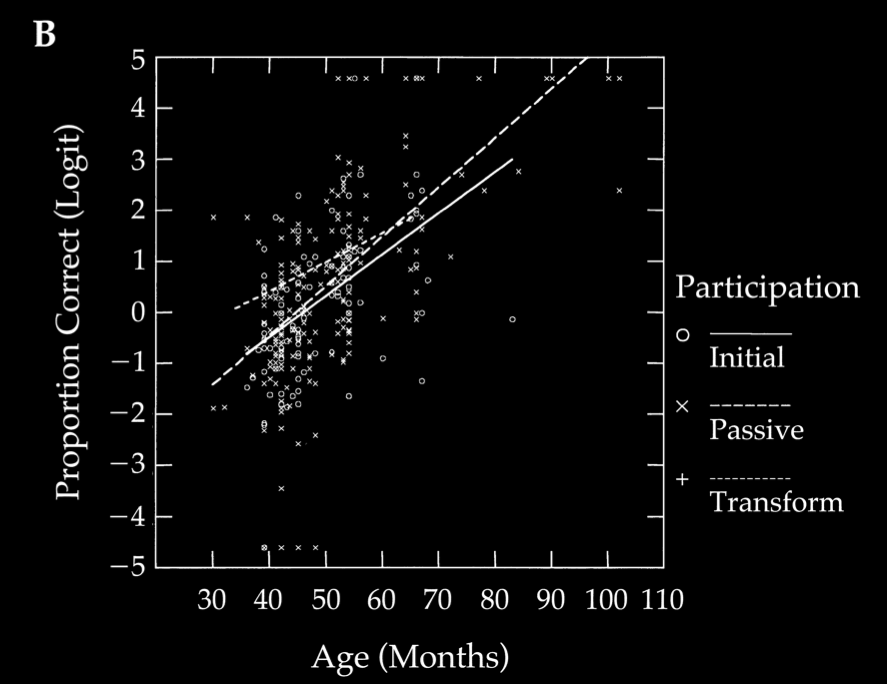

Wellman et al, 2001 figure 2A

Now there is clearly some variation here.

That's because different researchers implemented different versions of the original task.

We can use the meta-analysis of these experiments as a shortcut to finding out what sorts of factors affect children's performance.

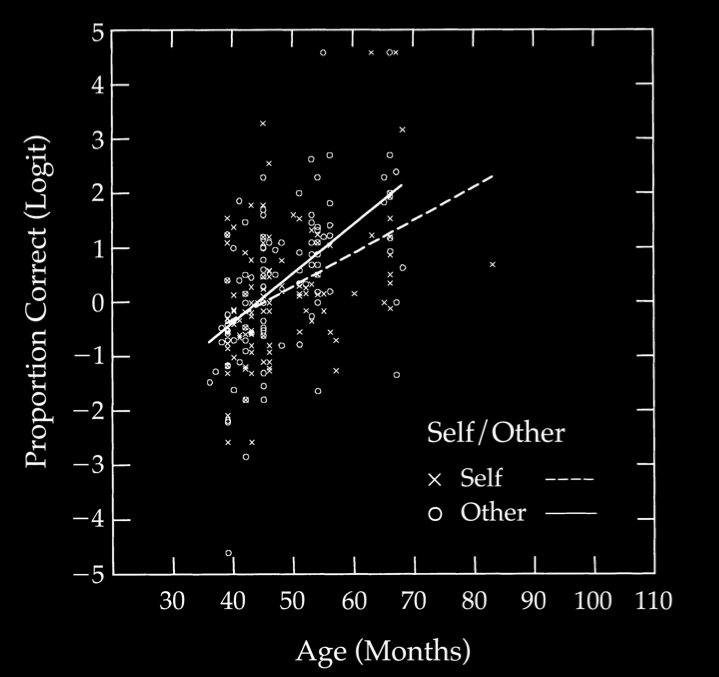

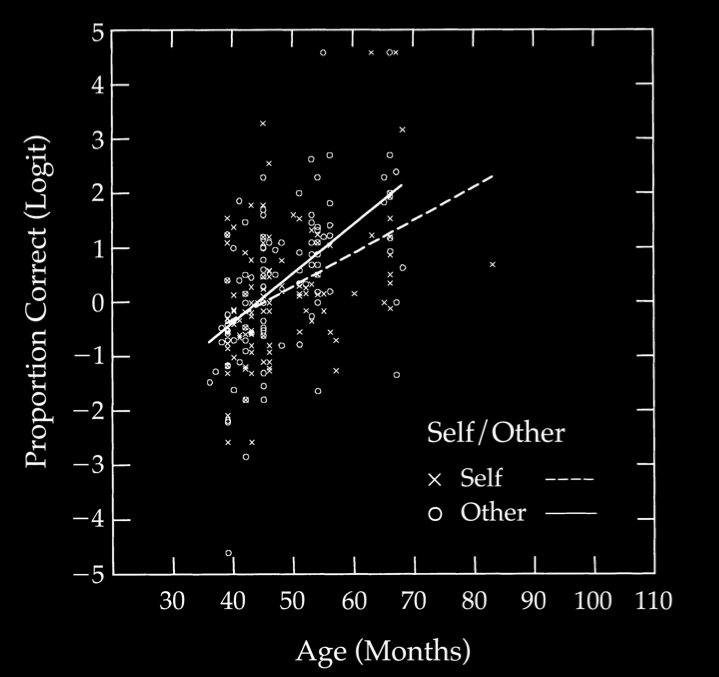

One factor that seems to make hardly any difference is whether you ask children about others' beliefs or their own beliefs.

To repeat, you get essentially the same results whether you ask children about others' beliefs or their own beliefs.

Children literally do not know their own minds.

Wellman et al, 2001 figure 5

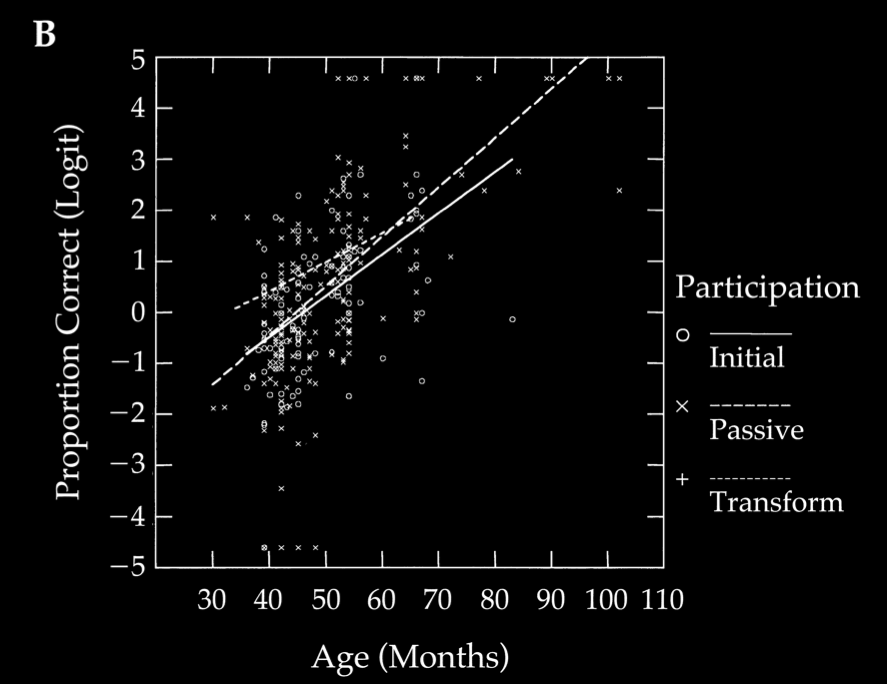

What happens if we involve the child by having her interact with the protagonist?

The task becomes easier for children of all ages, but the transition is essentially the same (participation does not interact with age Wellman, Cross, & Watson, 2001, p. \ 665-7).

Wellman et al, 2001 figure 6

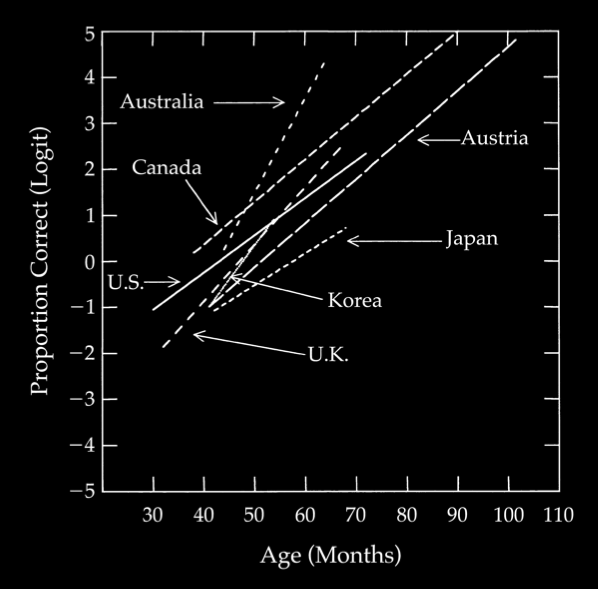

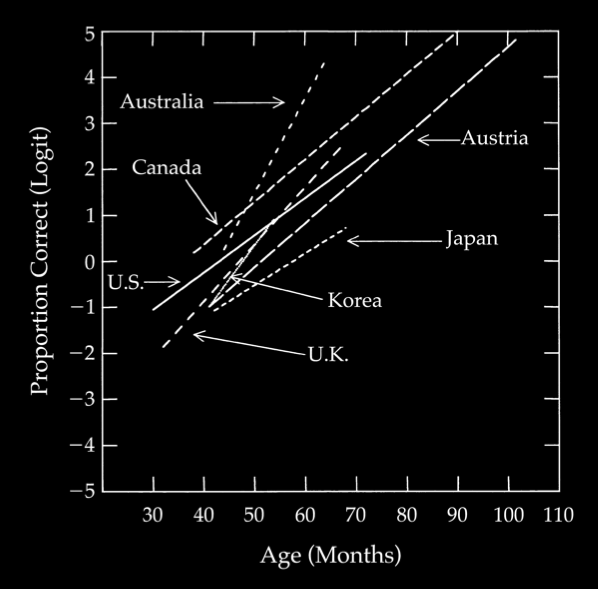

Finally, although there are some cultural differences, you get the same transition in seven diferent countries.

Wellman et al, 2001 figure 7

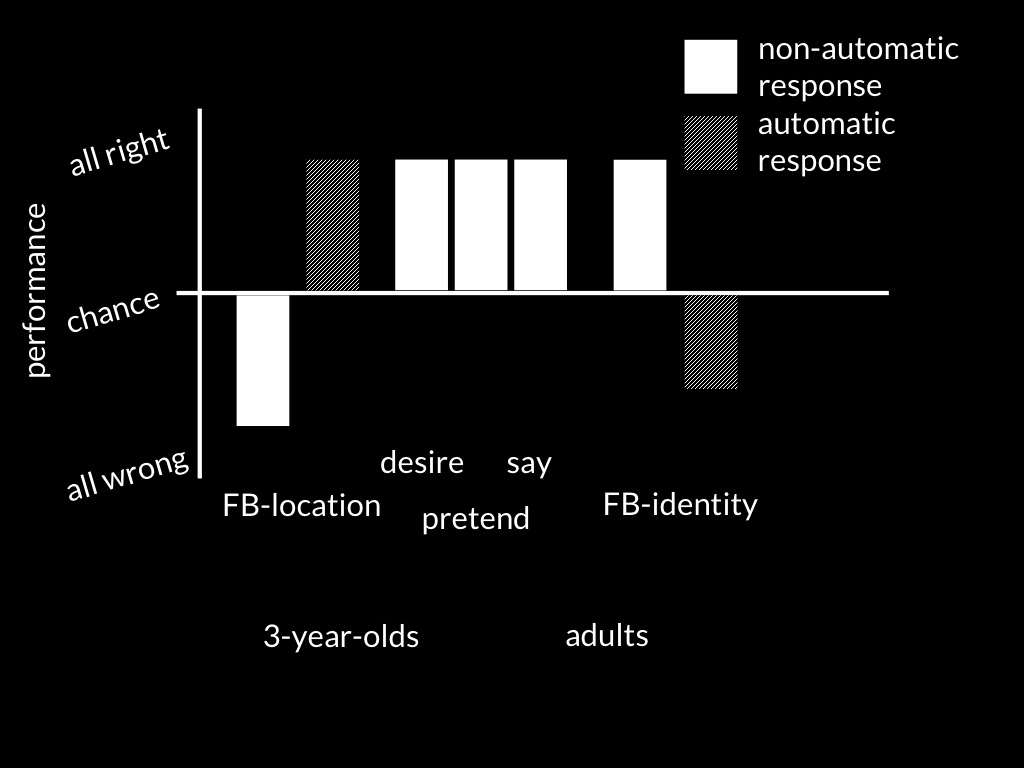

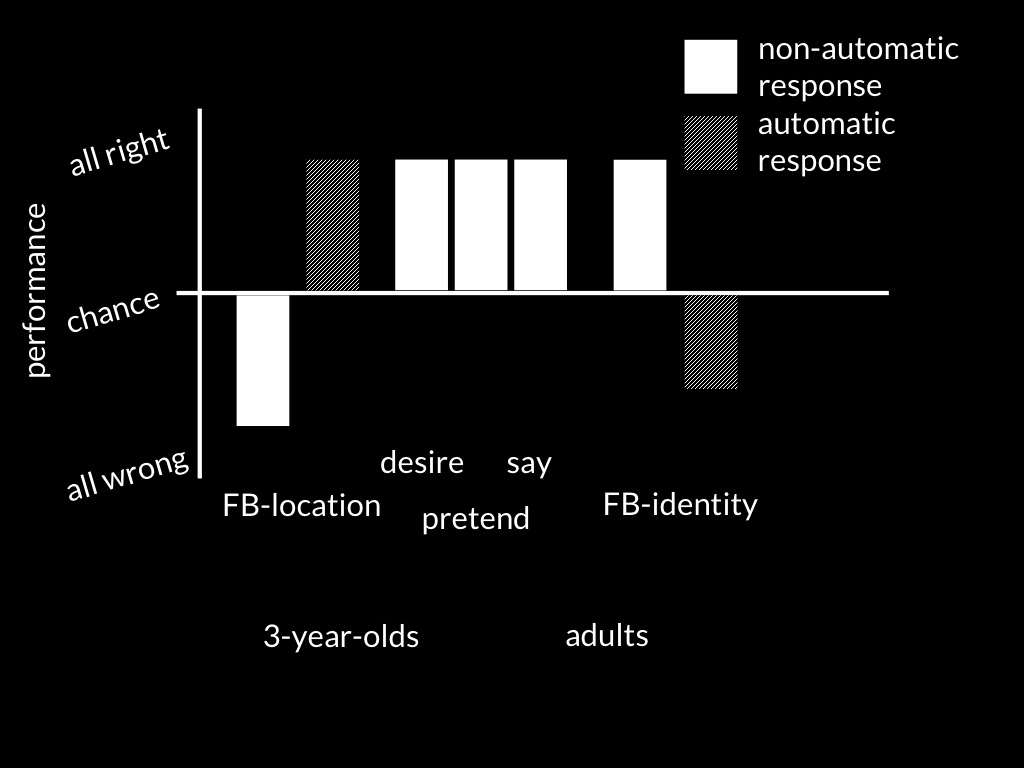

3-year-olds’ performance is not simply the result of performance factors.

After all, they succeed on structurally similar tasks about

pretence, saying or desiring.

[ASIDE ON EF] Further, changing the EF demands of a FB task doesn’t affect performance,

and, conversely, nor do differences between cultures in EF affect FB

performance.

Consistently with this, success on FB predicts later social competence

independently of EF.

But then what about the developmental relation between EF and FB performance?

It's emergence not performance (?).

challenge

Explain the emergence in development

of mindreading.

So our challenge was to explain the emergence of mindreading.

At this point, up until around, it seemed quite straightforward to most researchers.

We seemed to know that children are unaware of mental states until around four years.

And a lot of studies looked at which factors affect their acquiring this awareness.

These studies showed that executive function, language and rich forms of social

interaction are all important.

All of this supported something like the story that Sellars tells in his famous Myth of

Jones.

Sellars' Myth of Jones?

Link to Frith & Heyes cultural learning story.

but ...

But there was a big surprise in store for us.

Three-year-olds systematically fail to predict actions (Wimmer & Perner, 1983)

and desires (Astington & Gopnik, 1991) based on false beliefs; they similarly

fail to retrodict beliefs (Wimmer & Mayringer, 1998) and to select arguments

suitable for agents with false beliefs (Bartsch & London, 2000).

They fail some low-verbal and nonverbal false belief tasks

Call & Tomasello, 1999; Low, 2010; Krachun, Carpenter, Call, & Tomasello, 2009; Krachun, Carpenter, Call, & Tomasello, 2010; they fail whether the question concerns others' or their own (past)

false beliefs (Gopnik & Slaughter, 1991); and they fail whether they are

interacting or observing (Chandler, Fritz, & Hala, 1989).