Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Core Knowledge of Objects

Origins of Mind : 06

s.butterfill & [email protected]

When and how do humans first come to know simple facts about particular physical objects?

What have we found so far?

Three requirements

- segment objects

- represent objects as persisting (‘permanence’)

- track objects’ interactions

Principles of Object Perception

- cohesion—‘two surface points lie on the same object only if the points are linked by a path of connected surface points’

- boundedness—‘two surface points lie on distinct objects only if no path of connected surface points links them’

- rigidity—‘objects are interpreted as moving rigidly if such an interpretation exists’

- no action at a distance—‘separated objects are interpreted as moving independently of one another if such an interpretation exists’

Spelke, 1990

three requirements, one set of principles

Three Questions

1. How do four-month-old infants model physical objects?

2. What is the relation between the model and the infants?

3. What is the relation between the model and the things modelled (physical objects)?

What have we found so far? ... Apparently conflicting evidence.

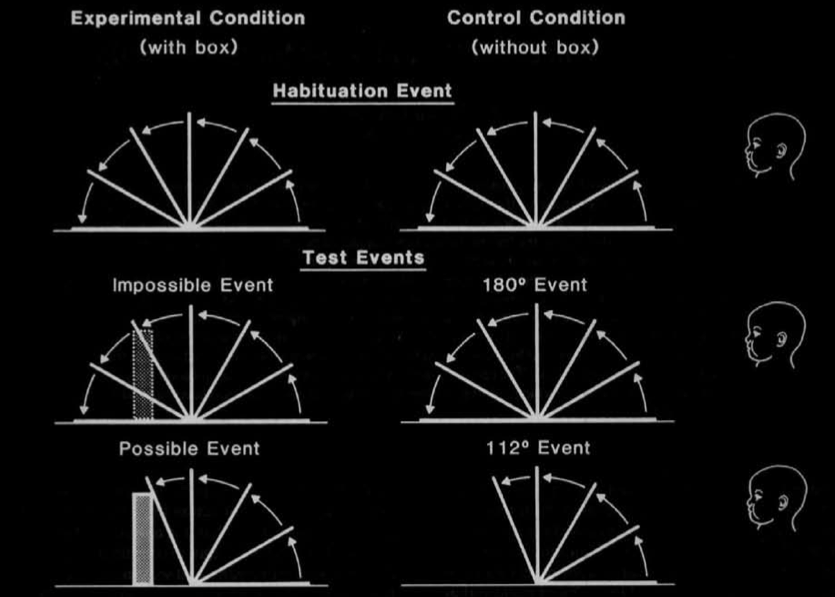

Baillargeon et al 1987, figure 1

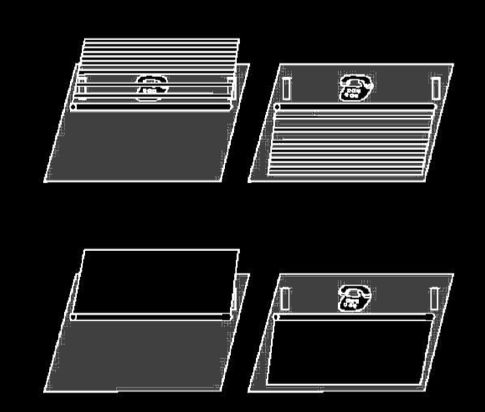

Shinskey and Munakata 2001, figure 1

| occlusion | endarkening | |

| violation-of-expectations | ✔ | ✘ |

| manual search | ✘ | ✔ |

Charles & Rivera (2009)

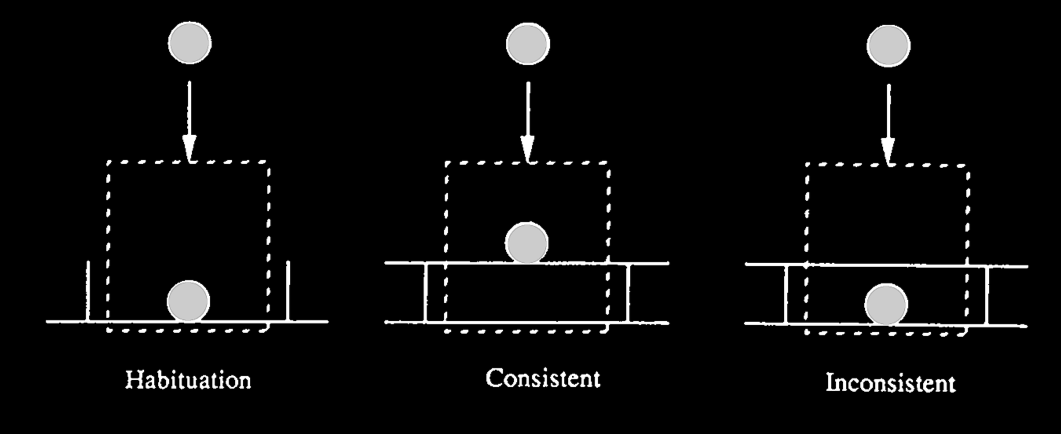

Spelke et al 1992, figure 2

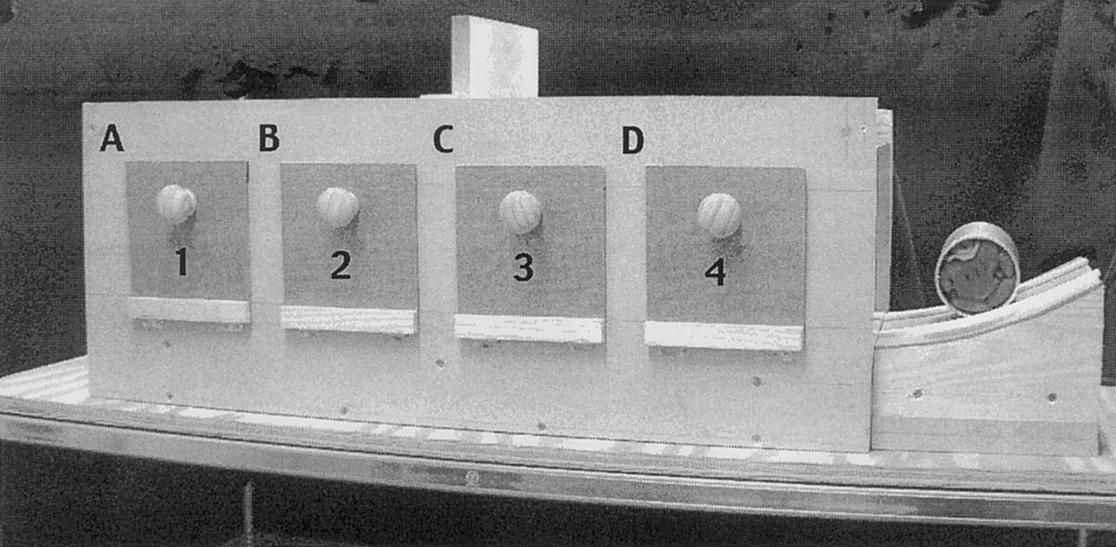

Hood et al 2003, figure 1

Three Questions

1. How do four-month-old infants model physical objects?

2. What is the relation between the model and the infants?

3. What is the relation between the model and the things modelled (physical objects)?

Two Candidate Answers to Q2

the Simple View ... generates incorrect predictions

the Core Knowledge View

Q1 What is the nature of infants’ earliest cognition of physical objects?

‘there is a third type of conceptual structure,

dubbed “core knowledge” ...

that differs systematically from both

sensory/perceptual representation[s] ... and ... knowledge.’

Carey, 2009 p. 10

Crude Picture of the Mind

- epistemic

(knowledge states) - broadly motoric

(motor representations of outcomes and affordances) - broadly perceptual

(visual, tactual, ... representations; object indexes ...)

Q1 What is the nature of infants’ earliest cognition of physical objects?

‘there is a third type of conceptual structure,

dubbed “core knowledge” ...

that differs systematically from both

sensory/perceptual representation[s] ... and ... knowledge.’

Carey, 2009 p. 10

core knowledge / core system

‘Just as humans are endowed with multiple, specialized perceptual systems, so we are endowed with multiple systems for representing and reasoning about entities of different kinds.’

Carey and Spelke, 1996 p. 517

‘core systems are

- largely innate

- encapsulated

- unchanging

- arising from phylogenetically old systems

- built upon the output of innate perceptual analyzers’

(Carey and Spelke 1996: 520)

representational format: iconic (Carey 2009)

Why postulate core knowledge?

The Simple View

The Core Knowledge View

| domain | evidence for knowledge in infancy | evidence against knowledge |

| colour | categories used in learning labels & functions | failure to use colour as a dimension in ‘same as’ judgements |

| physical objects | patterns of dishabituation and anticipatory looking | unreflected in planned action (may influence online control) |

| number | --""-- | --""-- |

| syntax | anticipatory looking | [as adults] |

| minds | reflected in anticipatory looking, communication, &c | not reflected in judgements about action, desire, ... |

Why postulate core knowledge?

The Simple View

The Core Knowledge View

‘Just as humans are endowed with multiple, specialized perceptual systems, so we are endowed with multiple systems for representing and reasoning about entities of different kinds.’

Carey and Spelke, 1996 p. 517

‘core systems are

- largely innate

- encapsulated

- unchanging

- arising from phylogenetically old systems

- built upon the output of innate perceptual analyzers’

(Carey and Spelke 1996: 520)

representational format: iconic (Carey 2009)

multiple definitions

‘there is a paucity of … data to suggest that they are the only or the best way of carving up the processing,

‘and it seems doubtful that the often long lists of correlated attributes should come as a package’

Adolphs (2010 p. 759)

‘we wonder whether the dichotomous characteristics used to define the two-system models are … perfectly correlated …

[and] whether a hybrid system that combines characteristics from both systems could not be … viable’

Keren and Schul (2009, p. 537)

‘the process architecture of social cognition is still very much in need of a detailed theory’

Adolphs (2010 p. 759)

Is definition by listing features (a) justified, and is it (b) compatible with the claim that core knowledge is explanatory?

Why do we need a notion like core knowledge?

| domain | evidence for knowledge in infancy | evidence against knowledge |

| colour | categories used in learning labels & functions | failure to use colour as a dimension in ‘same as’ judgements |

| physical objects | patterns of dishabituation and anticipatory looking | unreflected in planned action (may influence online control) |

| number | --""-- | --""-- |

| syntax | anticipatory looking | [as adults] |

| minds | reflected in anticipatory looking, communication, &c | not reflected in judgements about action, desire, ... |

| occlusion | endarkening | |

| violation-of-expectations | ✔ | ✘ |

| manual search | ✘ | ✔ |

Charles & Rivera (2009)

If this is what core knowledge is for, what features must core knowledge have?

‘Just as humans are endowed with multiple, specialized perceptual systems, so we are endowed with multiple systems for representing and reasoning about entities of different kinds.’

Carey and Spelke, 1996 p. 517

‘core systems are

- largely innate

- encapsulated

- unchanging

- arising from phylogenetically old systems

- built upon the output of innate perceptual analyzers’

(Carey and Spelke 1996: 520)

representational format: iconic (Carey 2009)

If this is what core knowledge is for, what features must core knowledge have?

not being knowledge

objections to the Core Knowledge View:

- multiple definitions

- justification for definition by list-of-features

- definition by list-of-features rules out explanation

- mismatch of definition to application

The Core Knowledge View

generates

no

relevant predictions.