Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Metacognitive Feelings Connect Object Indexes to Looking Behaviours

Metacognitive Feelings Connect Object Indexes to Looking Behaviours

[email protected]

object index operations

↓

? ? ? metacognitive feelings

↓

patterns in looking durations

‘metacognitive feelings ... allow a transition from the implicit-automatic mode to the explicit-controlled mode of operation.’

Koriat, 2000 p. 150

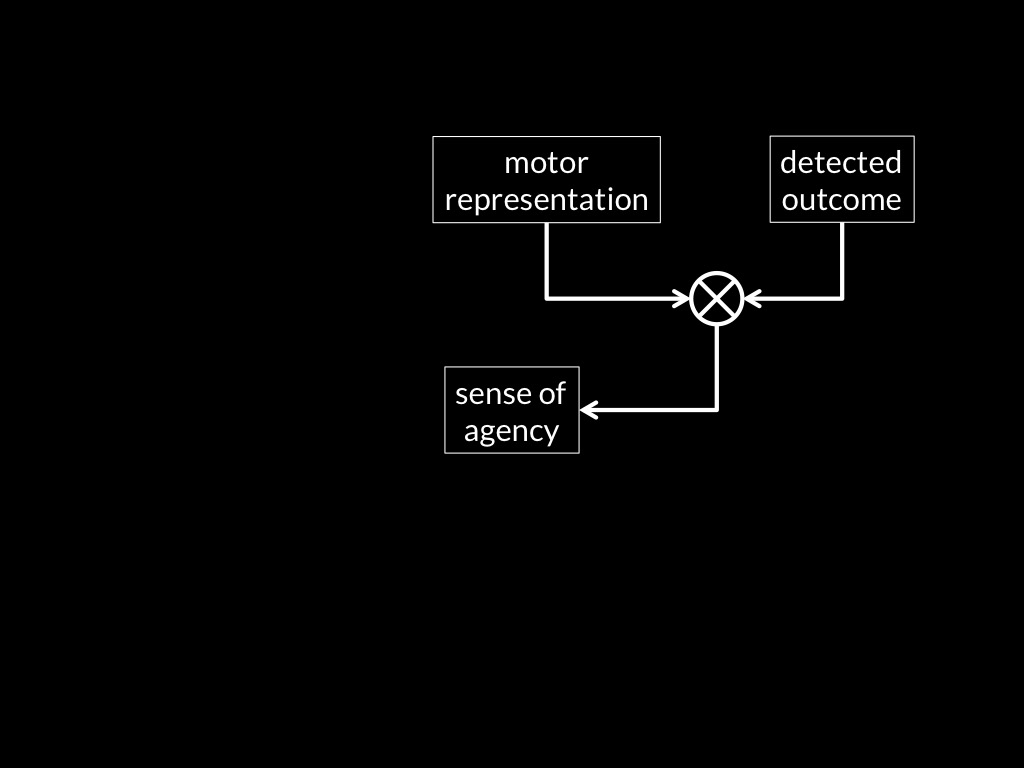

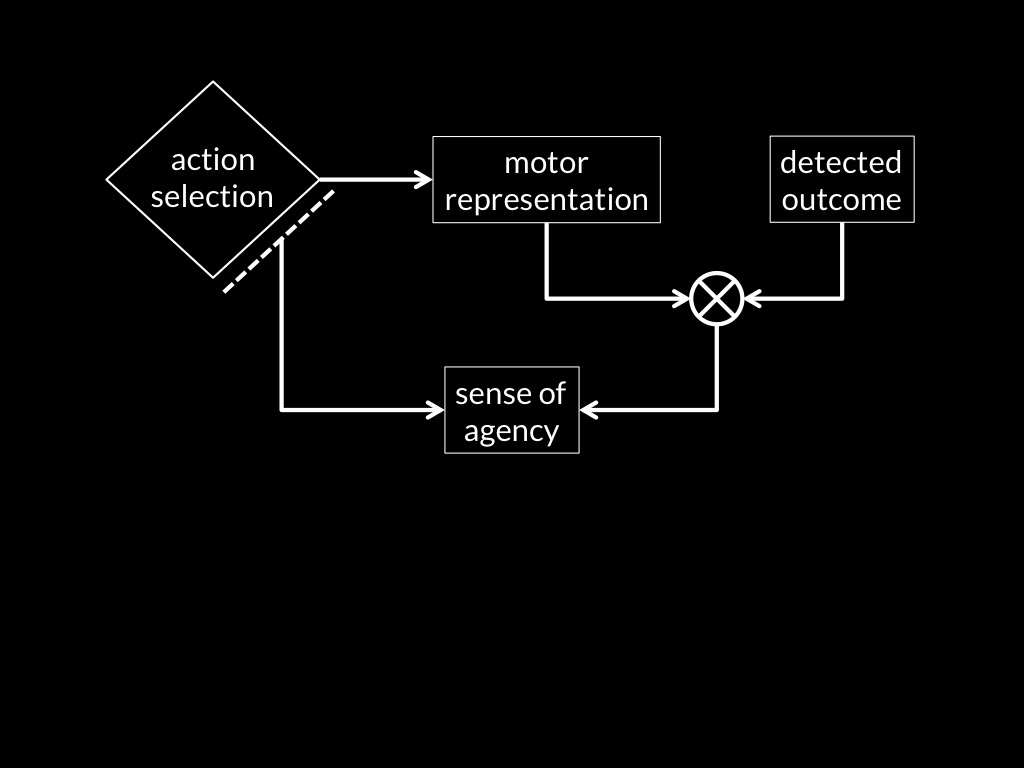

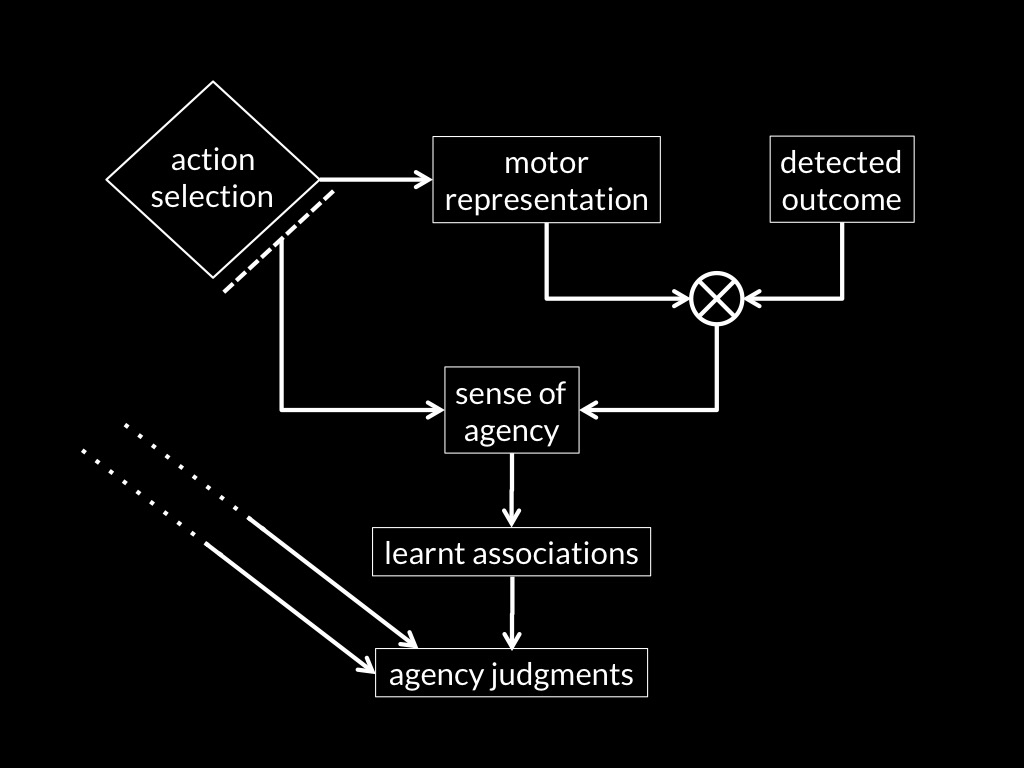

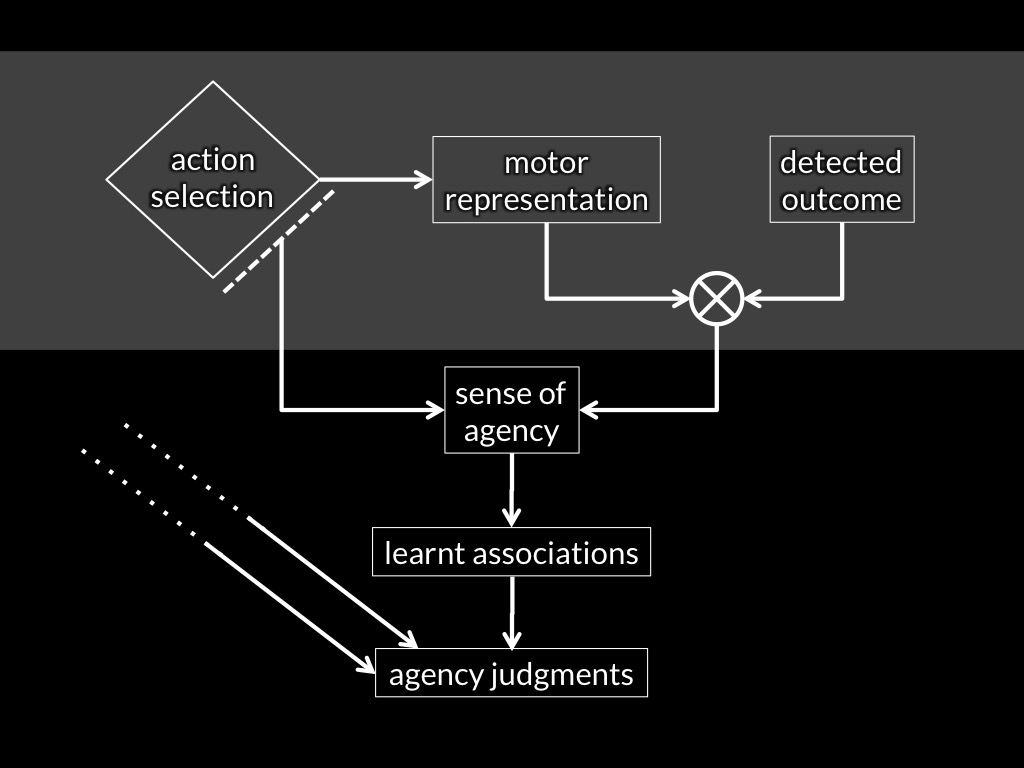

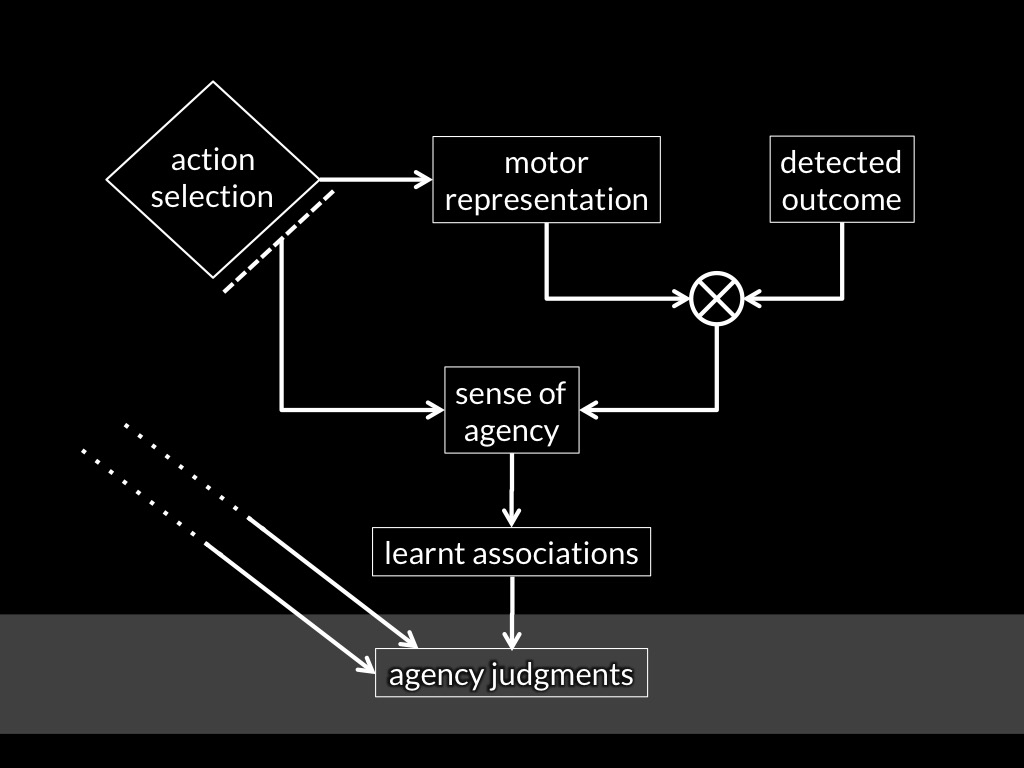

Adapted from Sidarus & Haggard, 2016 figure 5

Adapted from Sidarus & Haggard, 2016 figure 5

Metacognitive feelings

There are aspects of the overall phenomenal character of experiences which their subjects take to be informative about things that are only distantly related (if at all) to the things that those experiences intentionally relate the subject to.

Metacognitive feelings

can be thought of as

sensations.

Sensations are

- monadic properties of perceptual experiences

- individuated by their normal causes

- (so they do not involve an intentional relation)

- which alter the overall phenomenal character of those experiences

- in ways not determined by the experiences’ contents.

metacognitive feelings trigger beliefs only via associations.

metacognitive feelings

Thereare aspects of the overall phenomenal character of experiences which their subjects take to be informative about things that are only distantly related (if at all) to the things that those experiences intentionally relate the subject to.

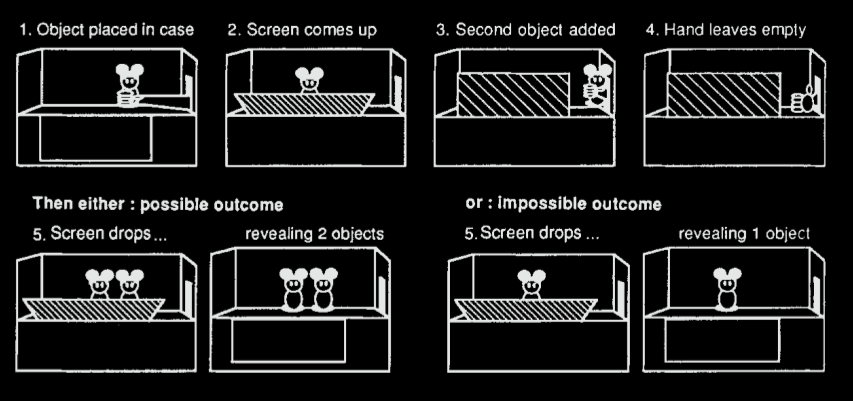

Wynn 1992, fig 1 (part)

feeling of surprise

‘the intensity of felt surprise is [...] influenced by [...]

the degree of the event’s interference with ongoing mental activity’

Reisenzein et al, 2000 p. 271; cf. Touroutoglou & Efklides, 2010

object index operations

↓

? ? ? metacognitive feelings

↓

patterns in looking durations

Objection

If object index operations produce metacognitive feelings,

wouldn’t these generate knowledge about object locations?

(And so generate the incorrect predictions that flow from ascribing knowledge of object locations?)

object index operations

↓

? ? ? metacognitive feelings

↓

patterns in looking durations