Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Motor Representation in Object Cognition

Motor Representation in Object Cognition

[email protected]

The CLSTX conjecture:

Five-month-olds’ abilities to track briefly unperceived objects

are not grounded on belief or knowledge:

instead

they are consequences of the operations of

a system of object indexes.

Leslie et al (1989); Scholl and Leslie (1999); Carey and Xu (2001)

| occlusion | endarkening | |

| violation-of-expectations | ✔ | ✘ |

| manual search | ✘ | ✔ |

Charles & Rivera (2009)

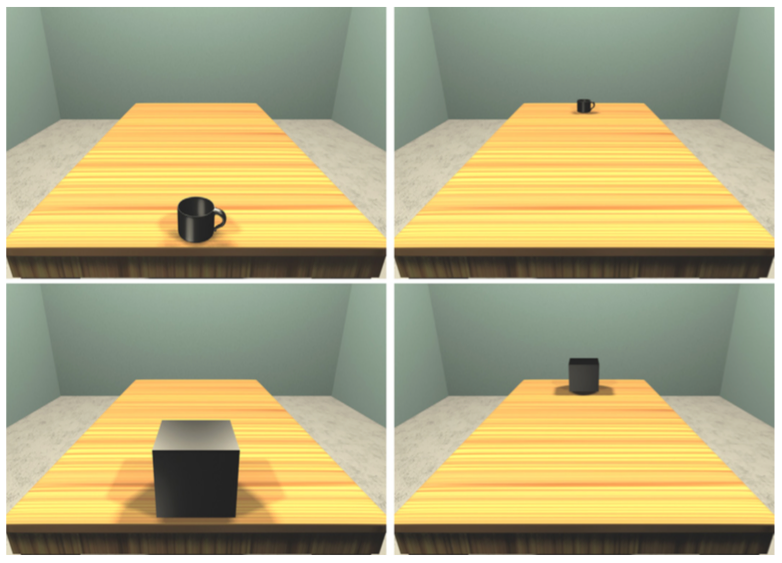

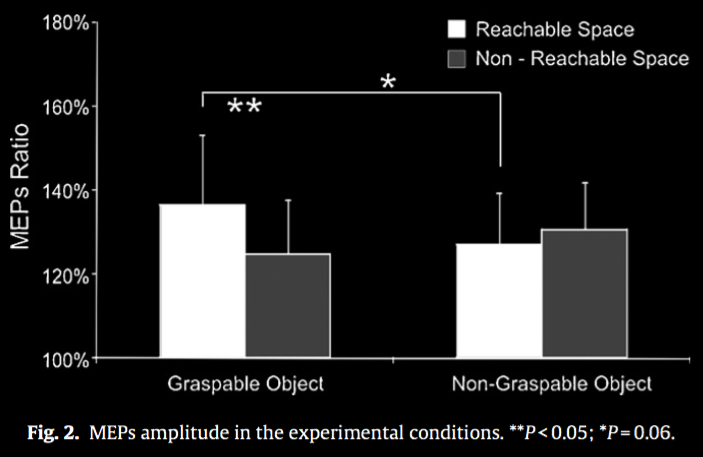

Cardellicchio, Sinigaglia & Costantini, 2011 figure 1

Cardellicchio, Sinigaglia & Costantini, 2011 figure 2

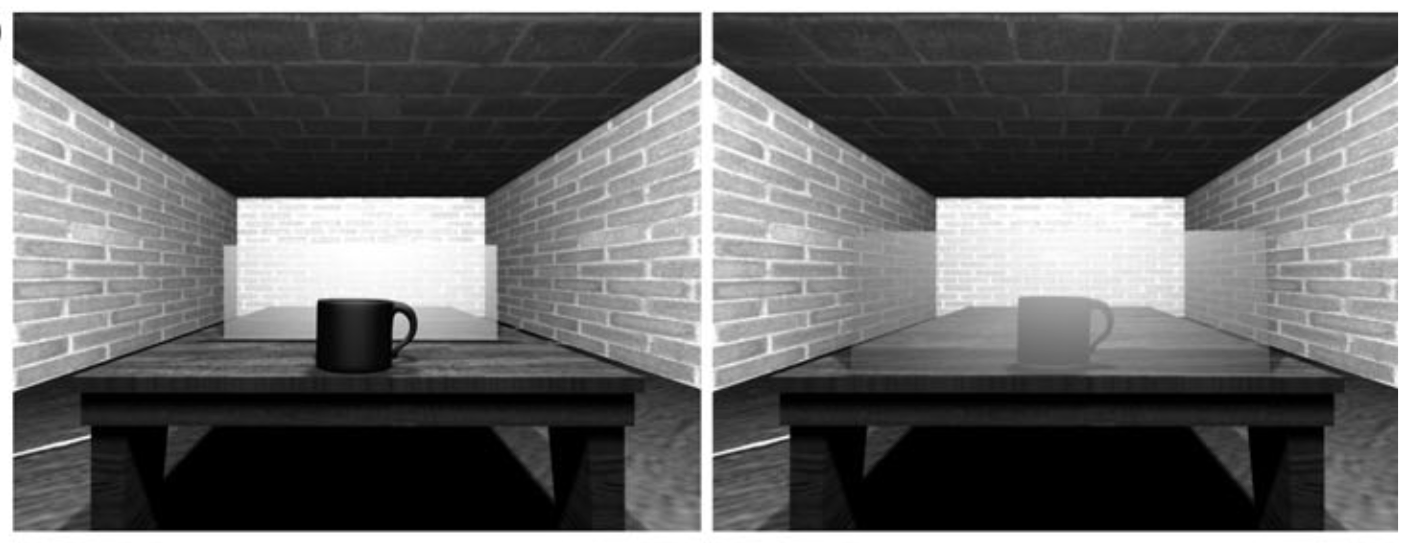

Costantini et al, 2010 figure 1B

Costantini et al, 2010 figure 1B

| survive occlusion | survive endarkening | |

| object index | ✔ | ✘ |

| motor representation | ✘ (barrier) | ✔ |

| occlusion | endarkening | |

| violation-of-expectations | ✔ | ✘ |

| manual search | ✘ (barrier) | ✔ |

The CLSTX conjecture:

Five-month-olds’ abilities to track briefly unperceived objects

are not grounded on belief or knowledge:

instead

they are consequences of the operations of

a system of object indexes.

Leslie et al (1989); Scholl and Leslie (1999); Carey and Xu (2001)

... and of a further, independent capacity to track physical objects which involves motor representations and processes.

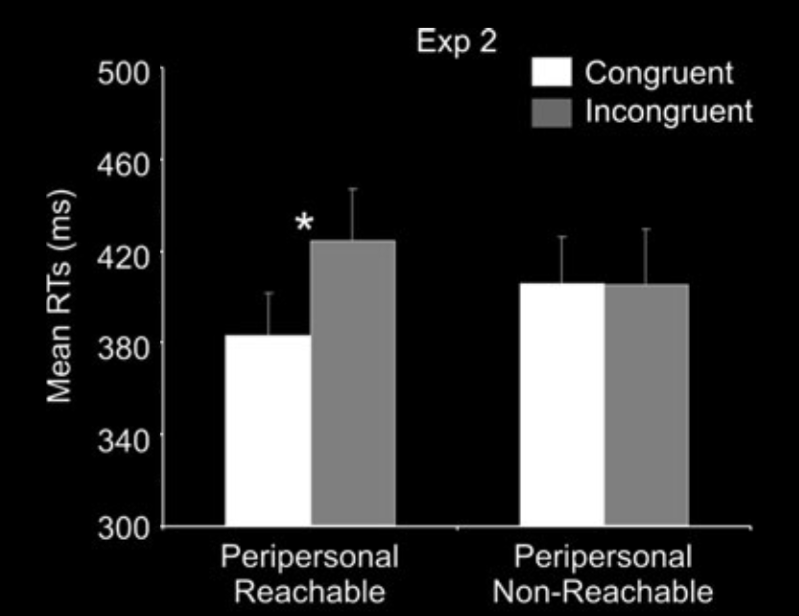

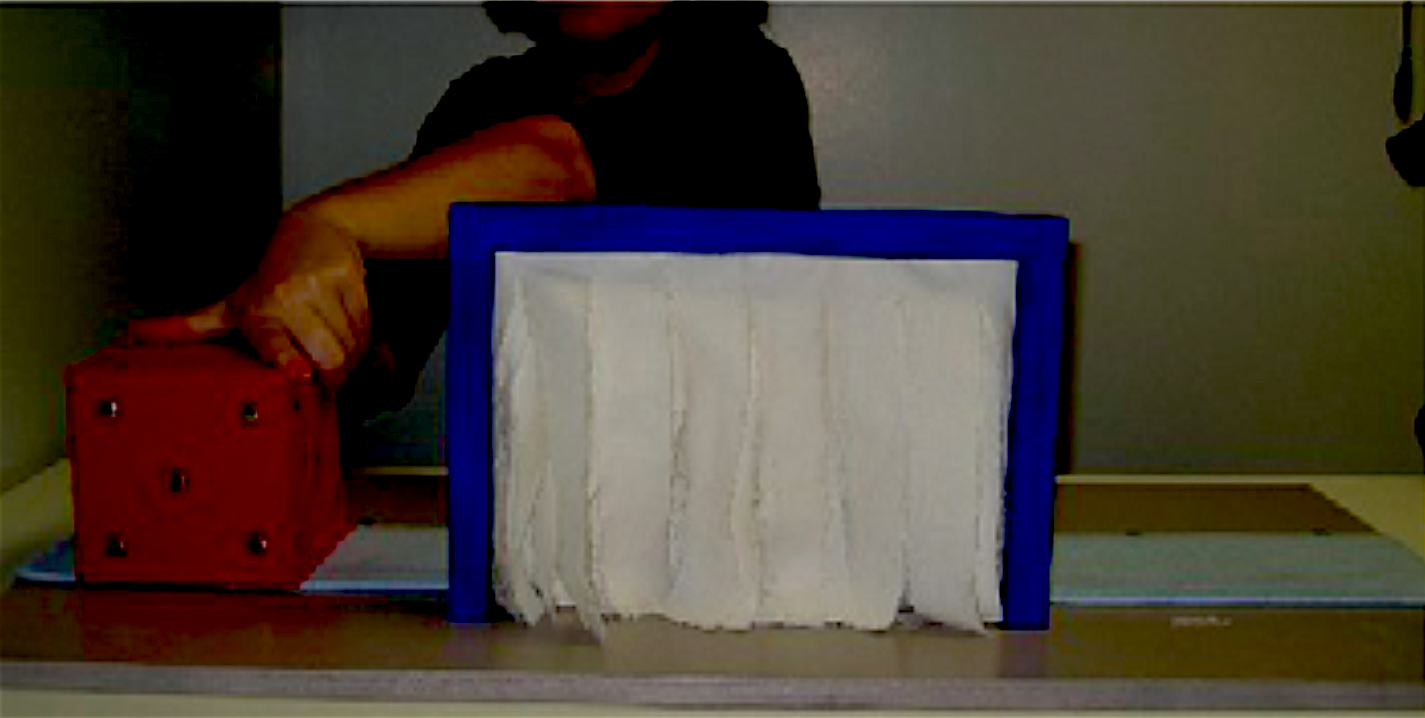

McCurry et al 2009, figure 1 (part)

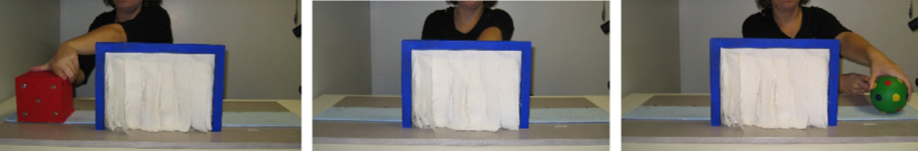

McCurry et al 2009, figure 1

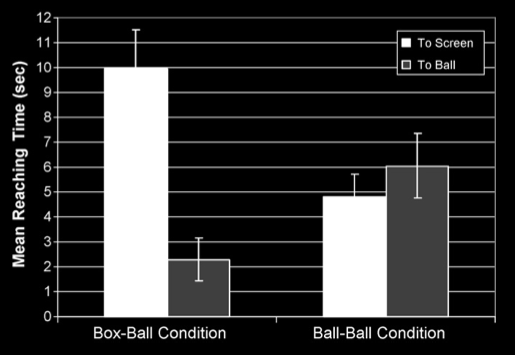

McCurry et al 2009, figure 2

The CLSTX conjecture:

Five-month-olds’ abilities to track briefly unperceived objects

are not grounded on belief or knowledge:

instead

they are consequences of the operations of

a system of object indexes.

Leslie et al (1989); Scholl and Leslie (1999); Carey and Xu (2001)

... and of a further, independent capacity to track physical objects which involves motor representations and processes.