Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

A Puzzle about Pointing

A Puzzle about Pointing

[email protected]

From around 11 or 12 months of age, humans spontaneously use pointing to ...

- request

- inform

- initiate joint engagement (‘Wow! That!’)

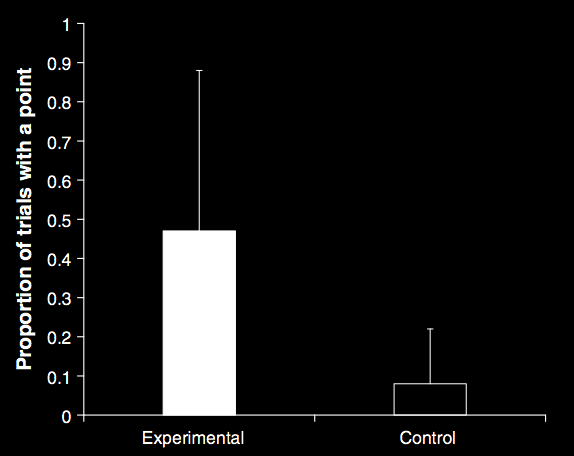

Liszkowski et al 2008, figure 3

Liszkowski et al 2008, figure 3

Liszkowski et al 2008, figure 5

From around 11 or 12 months of age, humans spontaneously use pointing to ...

- request

- inform

- initiate joint engagement (‘Wow! That!’)

How do infants understand pointing actions?

Hypothesis: ‘shared intentionality’ / communicative intention

shared intentionality

‘infant pointing is best understood---on many levels and in many ways---as depending on uniquely human skills and motivations for cooperation and shared intentionality, which enable such things as joint intentions and joint attention in truly collaborative interactions with others (Bratman, 1992; Searle, 1995).’

Tomasello et al (2007, p. 706)

Why suppose this?

Hare & Tomasello, 2004

‘to understand pointing, the subject needs to understand more than the individual goal-directed behaviour. She needs to understand that by pointing towards a location, the other attempts to communicate to her where a desired object is located’

Moll & Tomasello, 2007 p. 6

What is a communicative action?

First approximation: An action done with an intention to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention

(compare Grice 1989: chapter 14)

Hare & Tomasello, 2004

‘to understand pointing, the subject needs to understand more than the individual goal-directed behaviour. She needs to understand that by pointing towards a location, the other attempts to communicate to her where a desired object is located’

Moll & Tomasello, 2007 p. 6

First approximation: An action done with an intention to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention

(compare Grice 1989: chapter 14)

The confederate means something in pointing at the left box if she intends:

- #. that you open the left box;

- #. that you recognize that she intends (1), that you open the left box; and

- #. that your recognition that she intends (1) will be among your reasons for opening the left box.

(Compare Grice, 1967 p. 151; Neale, 1992 p. 544)

Inconsistent tetrad

1. 11- or 12-month-old infants produce and comprehend declarative pointing gestures.

2. Producing or comprehending pointing gestures involves understanding communicative actions.

3. A communicative action is an action done with an intention to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention.

4. Pointing facilitates the developmental emergence of sophisticated cognitive abilities including mindreading.