Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Limits on Infant Goal Tracking

limit:

infants in their first nine months of life

can only track the goals of an action

if they can perform a similar enough action

around the time the action occurs.

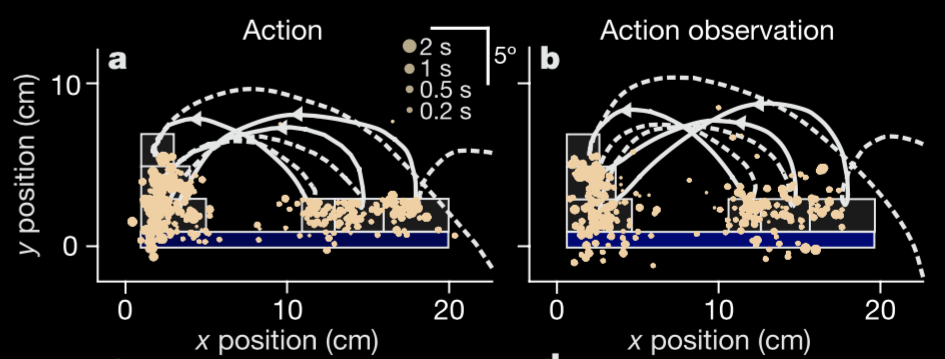

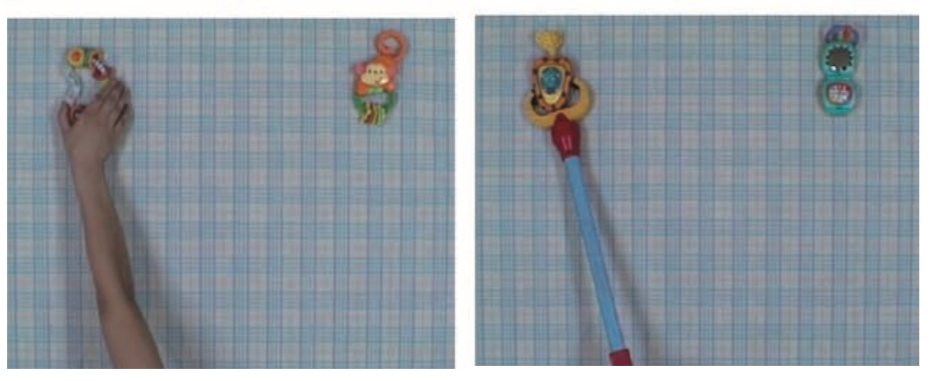

Flanagan and Johansson, 2003 figure 1 (part)

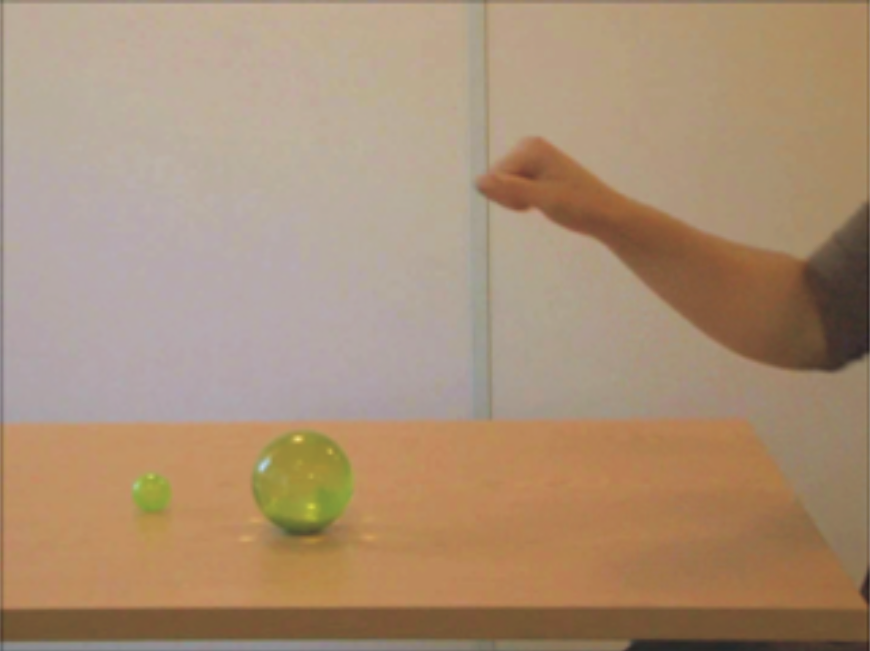

Kanakogi and Itakura, 2011 figure 1

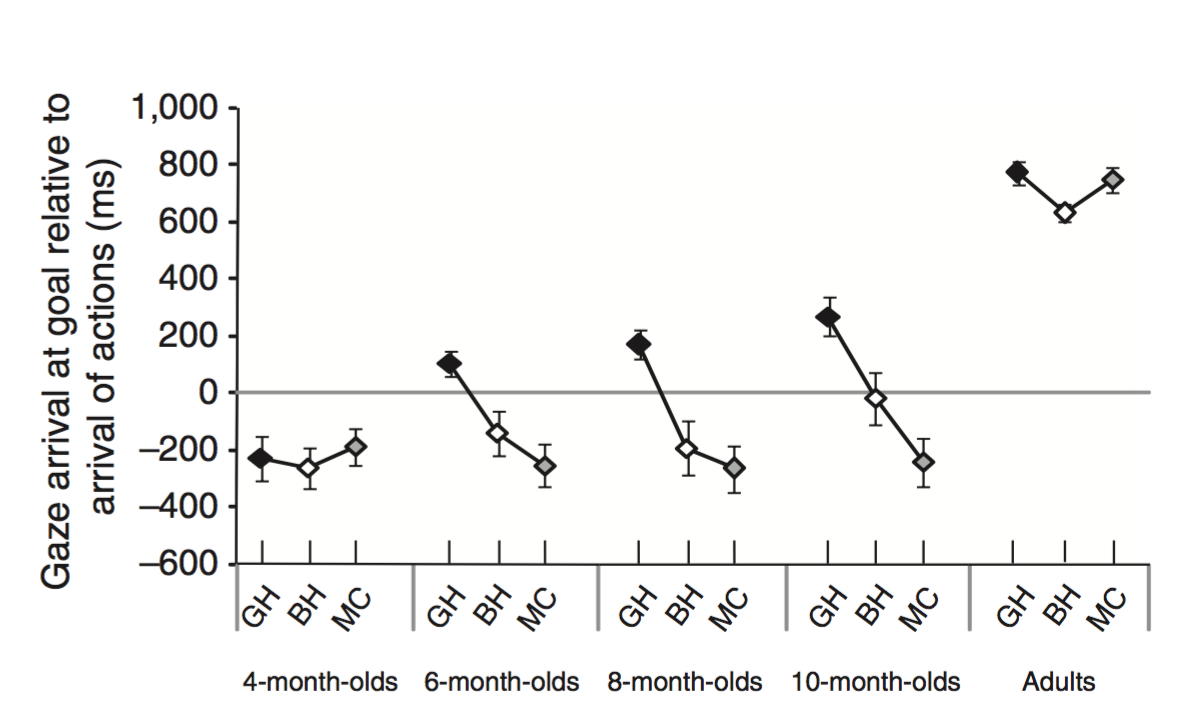

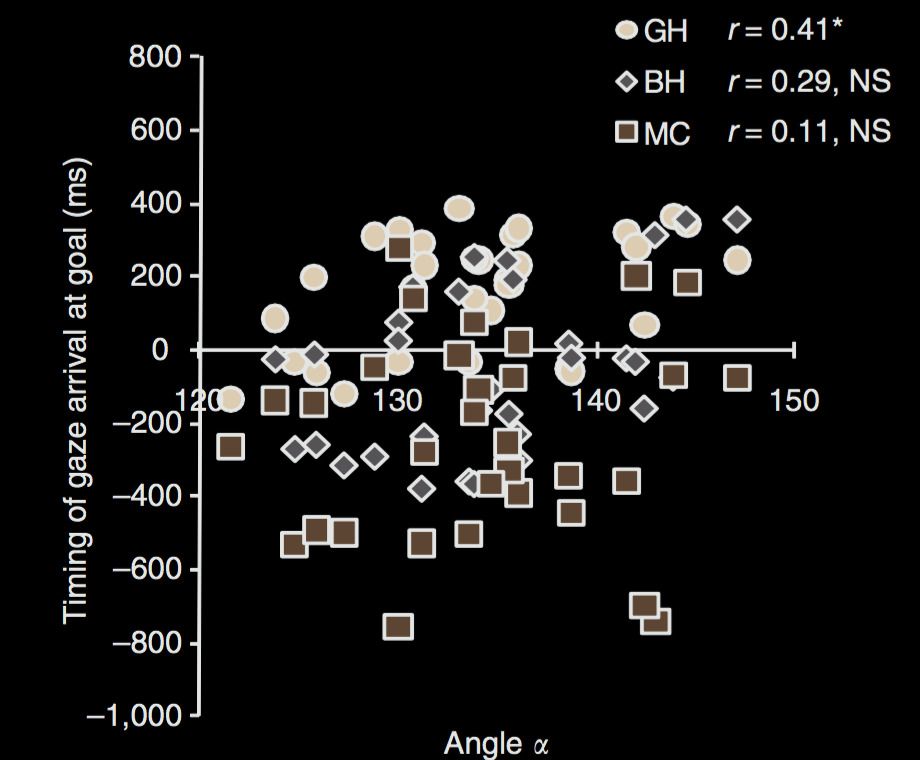

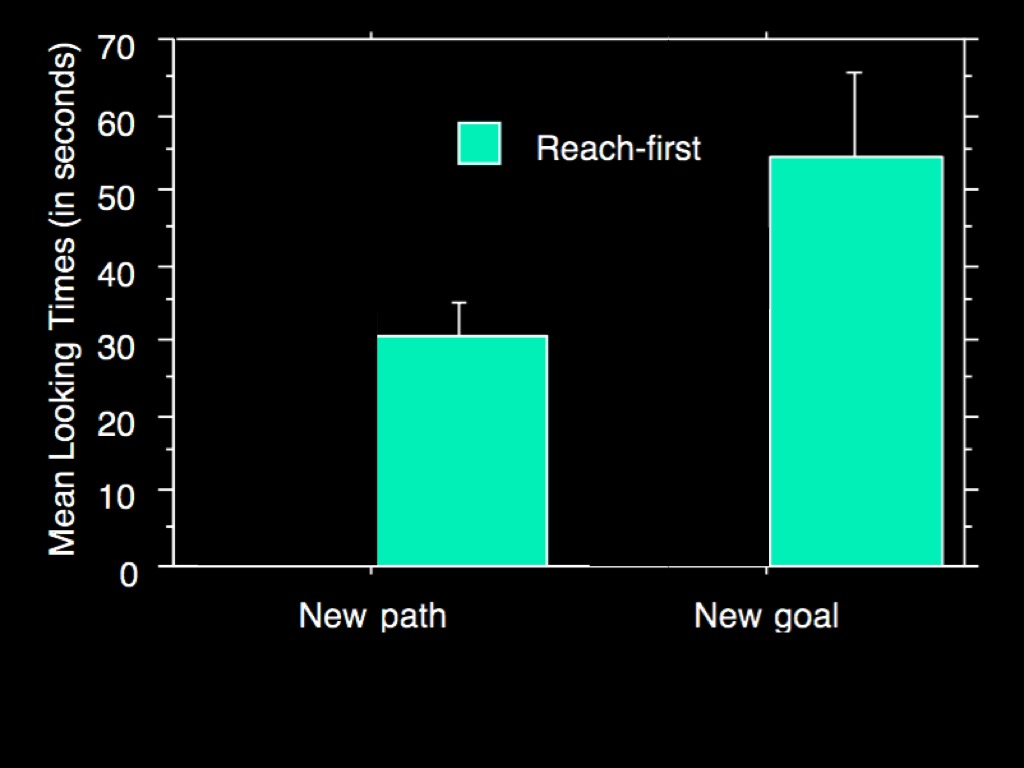

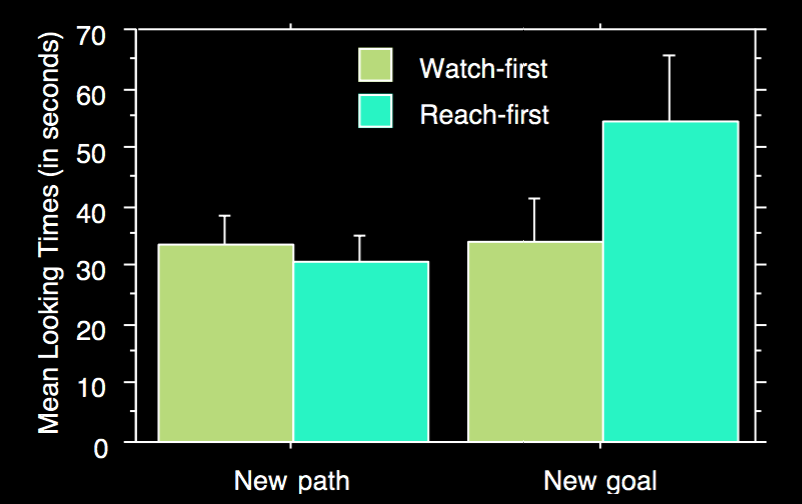

Kanakogi and Itakura, 2011 figure 5 (part)

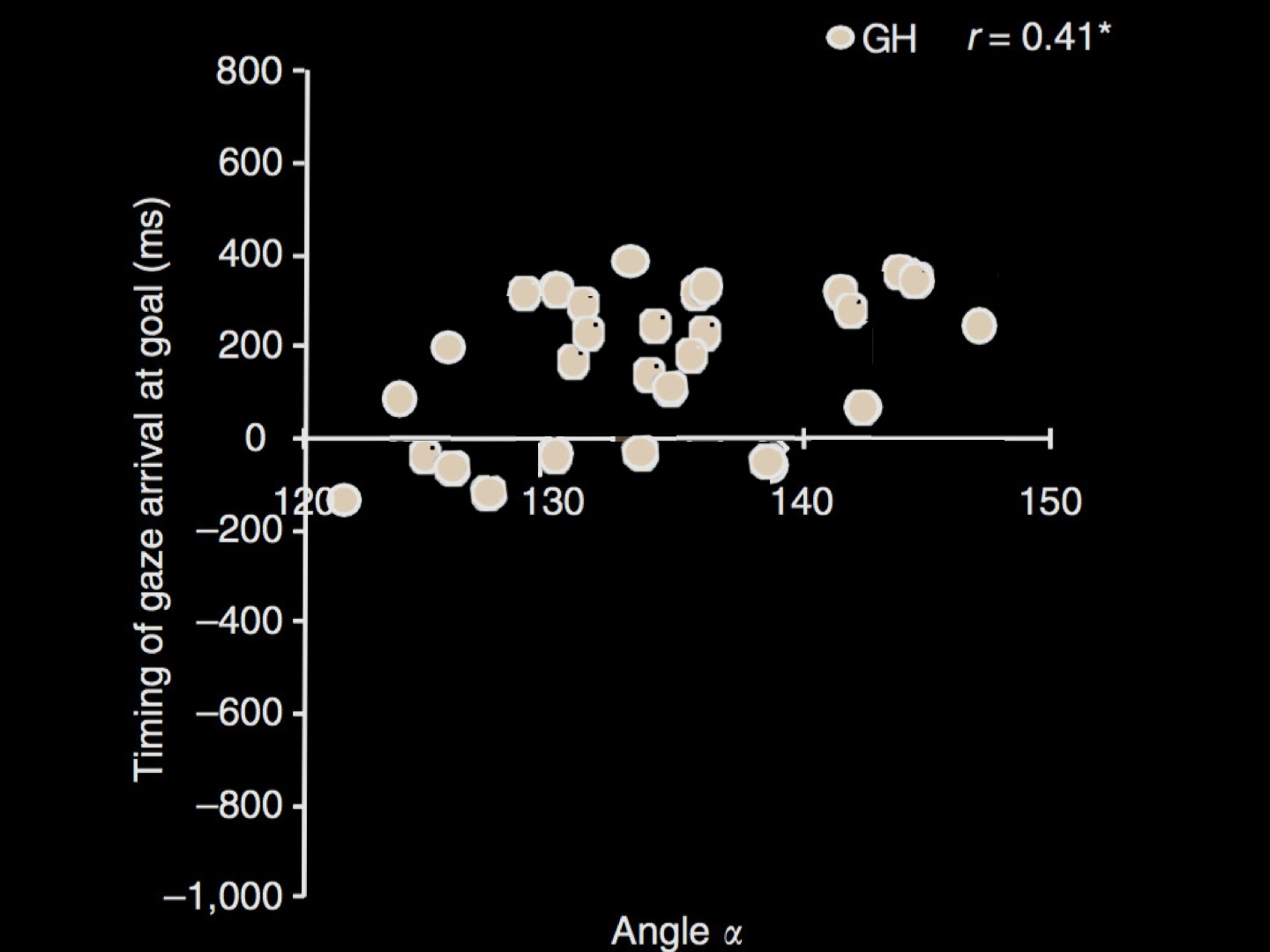

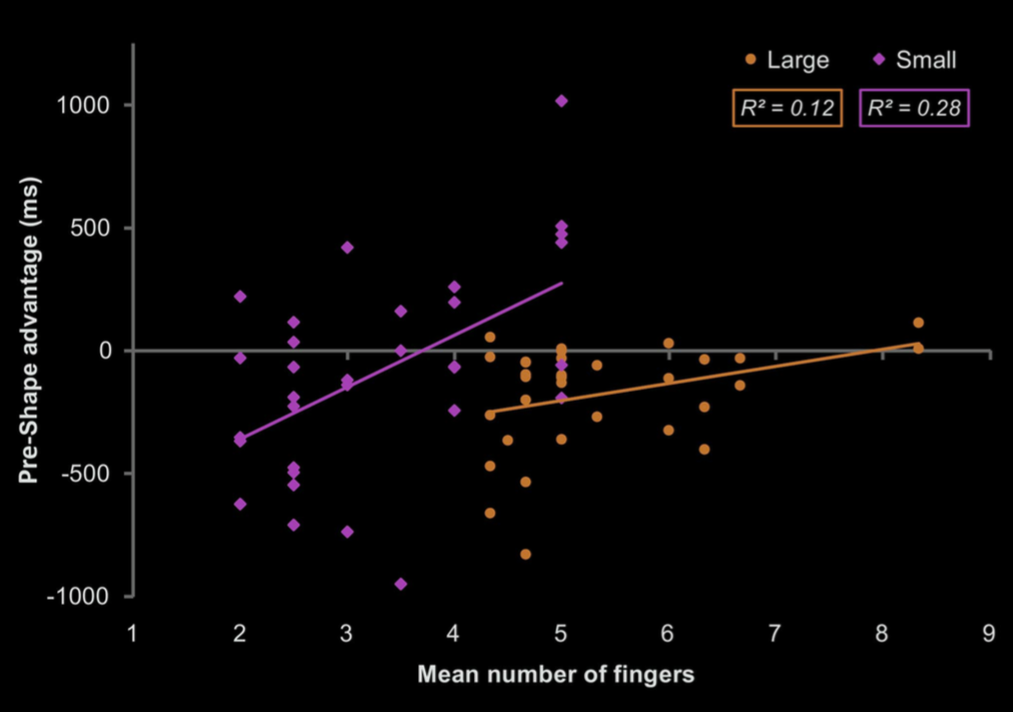

Ambrosini et al, 2013 figure 1 (part)

Ambrosini et al, 2013 figure 1 (part)

Ambrosini et al, 2013 figure 1 (part)

Ambrosini et al, 2013 figure 3

Kanakogi and Itakura, 2011 figure 1C (part)

Kanakogi and Itakura, 2011 figure 5

If infants can only track goals of actions they can perform, what happens if you intervene on their abilities to act?

Needham et al, 2002 / https://news.vanderbilt.edu/files/sticky-mittens.jpg

Sommerville, Woodward and Needham, 2005

Play wearing mittens then observe action.

vs

Observe action then play wearing mittens.

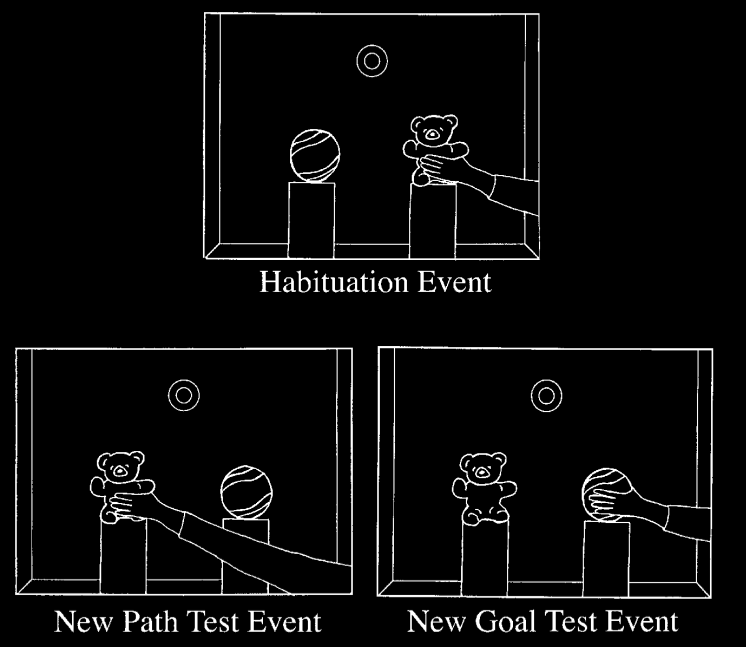

Woodward et al 2001, figure 1

Sommerville, Woodward and Needham, 2005 figure 3

Sommerville, Woodward and Needham, 2005 figure 3

objection

It’s not really grasping

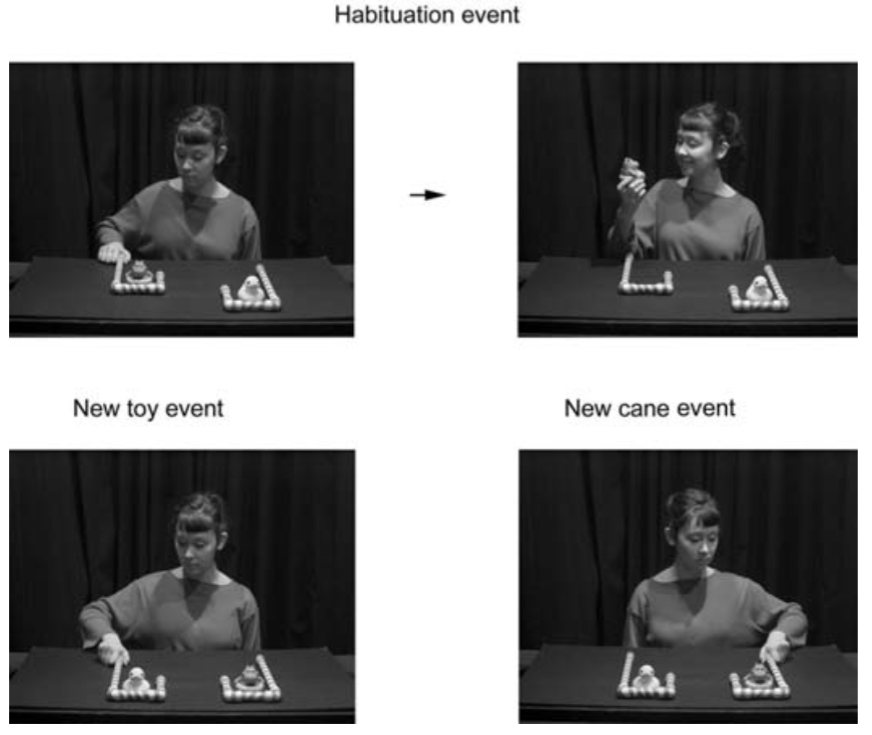

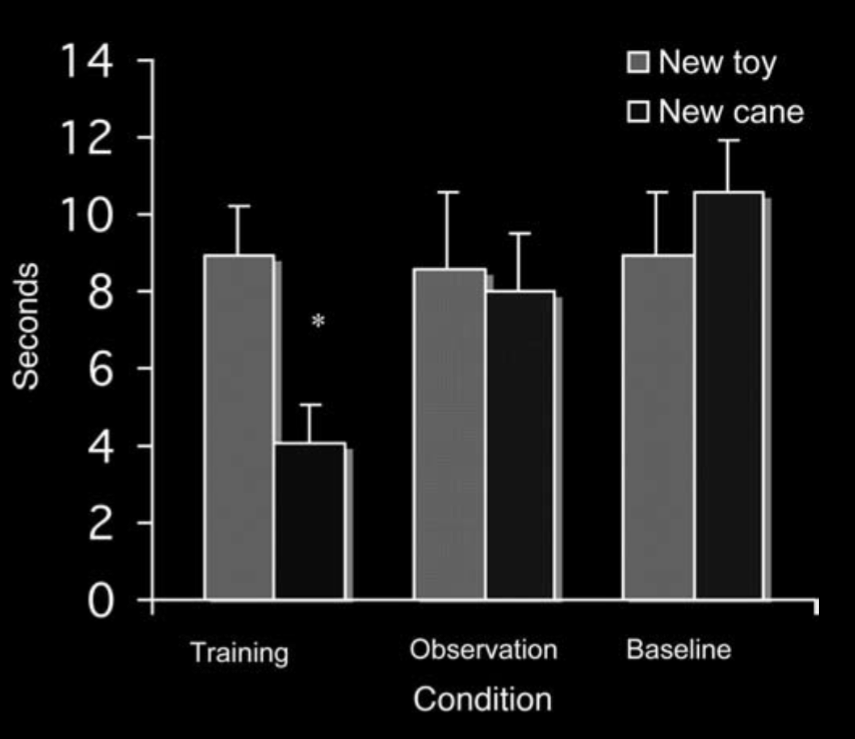

Sommerville et al 2008, figure 1

Sommerville et al 2008, figure 2

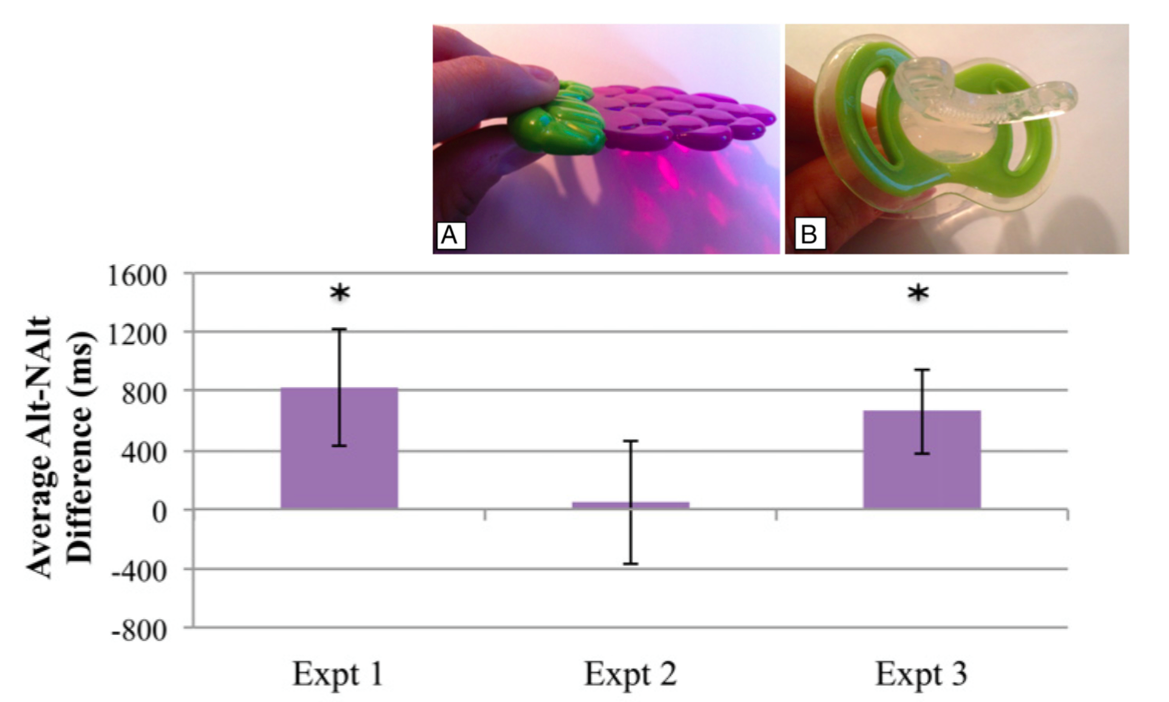

Bruderer et al, 2015 figures 1, 4

limit:

infants in their first nine months of life

can only track the goals of an action

if they can perform a similar enough action

around the time the action occurs.

Why?

In infants (and adults),

goal-tracking is limited by their abilities to act.